In the wave of Afrobeats global crossover moment, heralded by Wizkid’s Essence—Ckay became the first artist who wasn’t a superstar, to score a major smash hit with Love Nwantiti.

Burna Boy, Fireboy DML and Rema would go on to have their own moments with Last Last, Peru, Calm Down respectively, but those records flattered their already existing star powers as these artists had numerous continental hits and devoted fanbases. Ckay on the other hand had a about a song or two that could pass as sleeper hits, whilst Love Nwantiti was his first major hit, home and abroad. So what exactly is the relevance of this point that’s been iterated?

Well, it placed Ckay into the echelon of superstars due to the song’s immense success and demanded that he continued to operate in the strata of said superstars, when his talent or rather—brand of music isn’t exactly the most resonant type. His EPs, Ckay The First and Boyfriend are the clear sonic depictions of his brand of Afrobeats. It’s mid-tempo, Afro-R&B fusion that’s rhythmic and heavily reliant on melody, as opposed to lyricism and dynamism in delivery. And due to its unique sonic elements in the way Ckay wielded his voice and the nature of his topics, it passed as emo music or ’emo-afrobeats’ as he likes to call it.

His debut album, Sad Romance wasn’t exactly a phenomenal album, but it was a good offering that benefited from an artist knowing his strengths and maximizing its utility. On that album, Ckay prioritized ambience and a very immersive soundscape that allowed him to go places with his vocals and croon about his love escapades in ways that was sonically pleasing and rewarding. It was simply the best of Ckay’s artistry and he needn’t worry too much about mainstream resonance, because he was still riding off the high of Love Nwantiti’s success and Emiliano also being a digital hit. However, with his sophomore effort—Ckay knows he needs to score another hit song, or rather make an album that would appeal to the masses and that’s where the problems of this album rears its head.

Ckay’s talents aren’t the best suited to making good, resonant pop music like the Afrobeats popstars of his generation. He doesn’t have enough divergent artistry and swaggering charisma, like a Rema to attempt a reinvention of the wheel that would yield relative success. He doesn’t have the elaborate artsy branding and soulful, yet party-starting anthems like an Asake to redefine the sonic zeitgeist and operate on his own rules entirely. He doesn’t have the songwriting prowess and emotive themes in his music to make music, people can anchor their pain and reality in—like an Omah Lay or Fireboy DML.

Ckay simply makes rhythmic, ambience-reliant music that works to a tee as mood music, ideal for when all the lights are out and spirits aren’t exactly high. Even when all the right ingredients are in place, the music is simply not resonant or good enough to appeal to large demographics. He needs to understand this and not make another botched effort to deliver yet another mainstream album, that doesn’t do justice to his sonic identity and place him in soundscapes that expose his weaknesses.

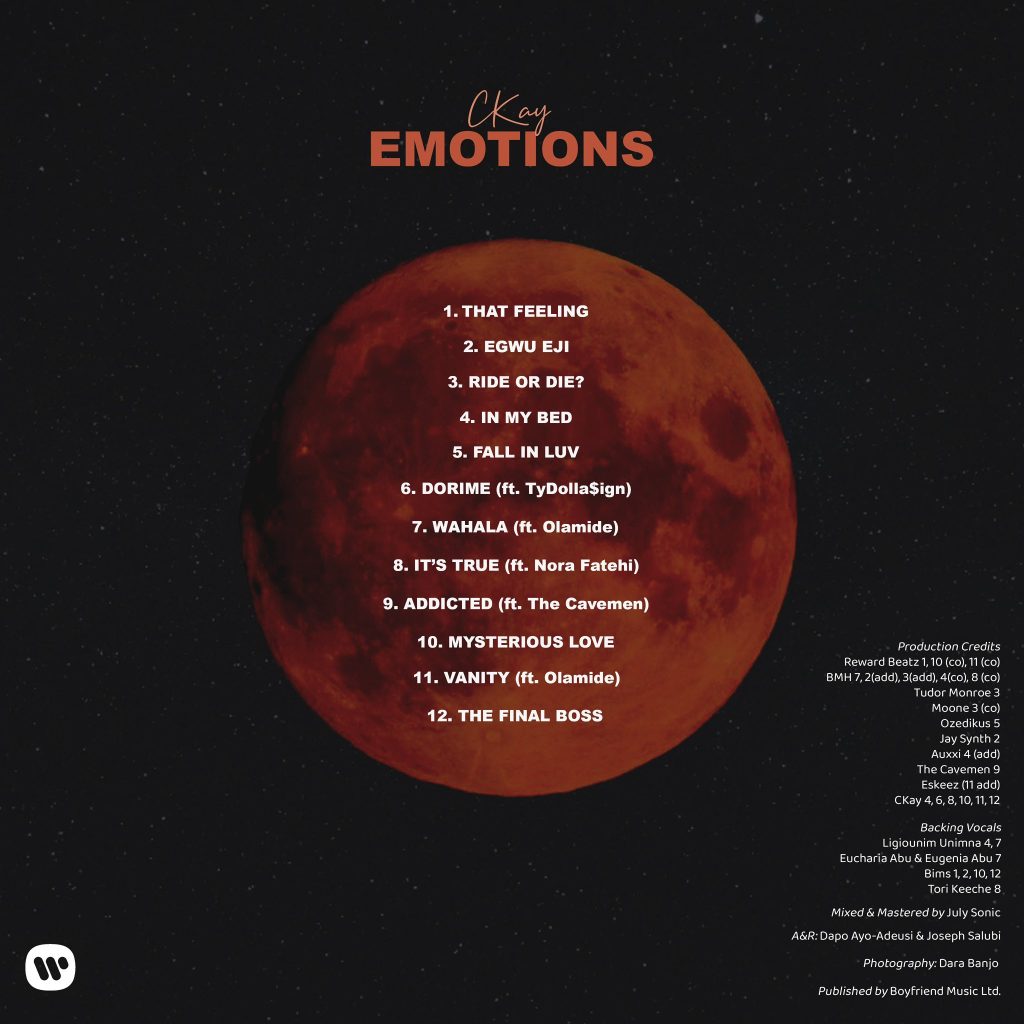

Album opener, That Feeling is emblematic of the issues of this album right out of the gate. The instrumental here is of course derived from the Amapiano-Afrobeats fusion soundscape, that has become a staple of the mainstream since Asake’s success in cementing it as the dominant pop sound. However, Ckay has faired quite well on beats like this on the deluxe version of Sad Romance. On this song though, he’s out of his depth and he doesn’t manage a single cadence that sticks.

His writing stands out also, as too on-the-nose. There is a certain level of skilled depth and layered narrative, that certified Afrobeats bad boys like Ruger, Lojay and Omah Lay bring to songs about their promiscuity and sexual conquests. The latter two are usually fighting demons, and use the sex as a coping mechanism whilst Ruger is just your textbook bad boy that loves the game for the thrill of it. Ckay’s lyrics doesn’t do anything to convince us that he’s on either side of the spectrum. He doesn’t hint at inner demons and his writing isn’t clever enough to convince us that he’s experienced at the thrill of it. It simply feels like he’s reading out all his bad intentions to a woman, who is too stupid to think for herself.

The less said about Egwu Eji, the better. It’s a mediocre version of Kcee’s smash Ojapiano. The song that it’s trying to be isn’t pretentious or ambitious in telling any serious narrative and simply lets the flute breathe and serenades you with the beautiful fusion of native instruments and contemporary pop elements. The flute on this song doesn’t have as much personality, and Ckay is once again unconvincing in selling this bad boy narrative with a very weak chorus, delivered with so little enthusiasm—you sort off get the vibe that even Ckay isn’t convinced himself.

Ride Or Die is an improvement on the two preceding tracks, but it’s far from a great song. Ckay does sound convincing on this track, as the departure from the Amapiano fusion into his usual mid-tempo territory suits him much better. And whilst the verses are decent, the chorus fails to stick a solid landing and leave a lasting impression that would aid its retaining value, like good choruses do. In My Bed is more of the same ingredients that work in Ride Or Die, and credit to Ckay as the chorus here does stick the landing and the production incorporates house elements that elevate the song. Ckay is also in his swooning bag and isn’t forcing the bad boy persona, so it’s easy to buy what he’s selling here. This is arguably the best song on the album.

When we get to Fall In Luv, it’s clear that this is the best three-track sequence on the project. Once again, it’s cut out of the same R&B fusion, midtempo sonic fabric of the last two songs, although there are subtle differences that trained ears would spot and appreciate. For most people though, it should be monotonous and rightly so. Lumping three alike tracks together on an album isn’t exactly the brightest decision. Dorime has some beautiful guitar chords that are so exotic and refreshing, that it paints a sonic backdrop of being somewhere tropical and tranquil. Unfortunately, neither Ckay nor Ty Dolla $ign put in a tight shift to do the beat justice. The chorus is too repetitive and lazy, and Ty Dolla $ign doesn’t do anything out of the box either.

Dorime segues right into Wahala, a song that is the much better version of it in all aspects. They are both built on the same sonic backdrop of quixotic guitar strings and Caribbean drum patterns, but Wahala has much more competent writing from Ckay in his verse and the chorus especially. Perhaps, it has to do with having Olamide on the track who is a legendary rapper that has written songs for numerous popstars. And unlike Ty, Olamide switches up his flows constantly and delivers a verse that is complimentary to Ckay’s narrative on the song, about the lustful dangers of the curves on a voluptuous woman.

As expected, this purple patch doesn’t last for long and the writing lapses rear their head again on It’s True. Ckay has never been an exceptional writer, but he has always been able to hold a strong narrative without resorting to one-too-many repetitive one liners, like he does a lot on this album. And from the song credits, you can glean that he’s working with a handful of writers that obviously don’t compliment his artistry. This is a basic A&R problem that shouldn’t be happening to an artist of his status. Nora Fatehi’s vocals being rich and calming is probably the only good takeaway from this song.

The Cavemen do their thing on Addicted with their sultry vocals and effervescent production, that compliments Ckay because his style is heavily reliant on sonic atmosphere and vocal delivery. This is one of the few good A&R decisions that pay off on this LP. Whilst the writing and narrative is still weak here, as neither artists are saying anything in particular that stand out—it works because it’s sonically pleasing and soothing. Mysterious Love is more of the same Amapiano-fusion and flute marriage that didn’t work on Egwu Eji and still doesn’t work here. Although this song is slightly more bearable than Egwu Eji, as the writing isn’t as bad because once again Ckay isn’t forcing the bad boy persona.

On Vanity, Ckay does something different topically and speaks about his rise to stardom and overcoming obstacles on the way to the top. Of course, it isn’t an Afrobeats album if there isn’t a song bordering on the spirit of gratitude and succeeding against all odds. Credit to Ckay for not doing the stereotypical thing of placing the song as the first or last song on the LP, although it’s second to last. Olamide isn’t as dynamic as he was on Wahala, but his rhyme schemes remain tight and that would be enough for most.

Ckay’s The Final Boss is his own take at embodying the villain narrative, but the execution falls flat and pales in comparison to Rema’s Villain, a more nuanced example of the trope done right. Ckay doesn’t have half the variance of Rema’s expansive delivery on the song and the production isn’t as grand and maximalist as P.prime’s instrumental, that was crucial in building up the song’s inherent dark and nihilistic vibe. Ckay’s vocals aren’t convincing either, as it’s a tad high pitched and so when he calls himself the “boss” in an action film, it’s just hard to take him seriously.

If Emotions was Ckay’s debut album, then it would have been easy to write it off as a fledgling artist who was still maturing and was yet to master the full scope of his artistry. But Sad Romance was an album that capitalized on his strengths, so on Emotions it’s clear Ckay is having an identity crisis in a bid to make mainstream music. The bad boy persona isn’t convincing, as a result of poor writing. The Amapiano-fusion doesn’t compliment his artistry and the A&Ring of the album fails to mask its problems.

On an album titled Emotions, he fails to tap into emotions and make music that is emotive, which is ironically his greatest strength as an artist. If the cost of making Afro-pop music would cost him this much, perhaps it’s time to return to return to what works. And if he insists on making pop music nonetheless, then he would need to unearth a formular that works because this one doesn’t.

Final Verdict:

Sonic Cohesion & Transitions: 1.5/2

Expansive Production: 1.3/2

Songwriting: 0.5/2

Delivery: 0.7/2

Optimal Track Sequencing: 1.3/2

Total: 5.3/10